|

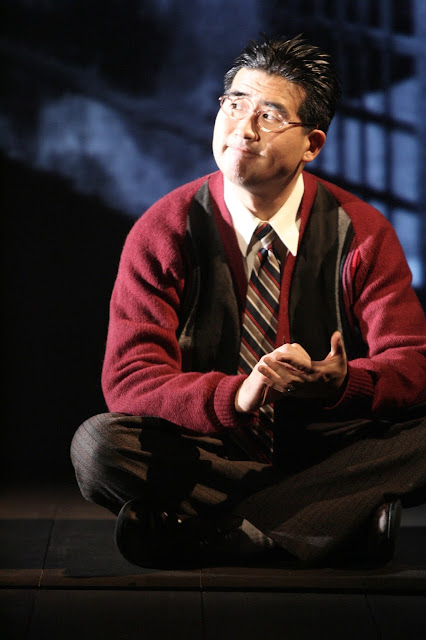

| Actor Ryun Yu in the role of Gordon Hirabuyashi at ACT Photo: Michael Lamont |

When I attended the press opening of Hold These Truths—a play by Jeanne Sakata about the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII—my body might have been at ACT-A Contemporary Theatre, in Seattle, but my mind was in the strawberry fields across the road from my childhood home. We lived on nearby Vashon Island, and our Japanese-American neighbors owned those fields.

By my early teens, I was aware of the fact that this fine family, the Matsudas, had spent time in internment camps during WWII, even while their son served in the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, but no one talked about this during the 1960s when I picked strawberries on the Matsuda farm for a summer job, alongside my siblings and friends. It was not a topic of conversation in our home either, although initially it must have deeply upset my parents. I knew they thought it wrong. I was born as next to the youngest in a large family, but the Matsudas had always been friends, good neighbors, and went to the same church. I was brought up to respect them. I could tell that this past, the years when their modest farm house stood empty, represented a touchy subject, carrying a sense of embarrassment and shame, but it was before my time. If there had been any outrage in the community over this injustice, little trace of it remained evident during my youth.

As an adult, I read a book published in 2005 by a member of the Matsuda family, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald. She gave it the title of Looking Like the Enemy-My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps. Mary was a teenager when she, along with her parents and brother, were abruptly evacuated from their island home, as were as many as 120,000 other Japanese-Americans on the West Coast. After I read her book, I loaned it to my father, who was by then in his nineties. I will never forget how profoundly it affected him. When he read about how the Matsudas purposefully destroyed their precious family heirlooms and photographs to avoid any appearance of loyalty to Japan, he felt extremely sad, saying if he had only known he would have gladly stored and protected their belongings for them until the war's end. Whether of not it occurred to my parents or others in our community to dig into the truths of our neighbors horrible and unjust experiences, or whether or not they stopped to imagine the sacrifices involved, I cannot say. I know my father and others seemed to believe the internment actually might have protected the Japanese from violence, but who can say? Surely that protection could have been provided in a more humane way.

My father was old enough to remember the arrival of Japanese families on the island during the 1920s and how well they were accepted, how their children and the island's other children happily attended school together and became good friends. By 1936, 37 Japanese families lived on Vashon. All contributed to and participated in that small society. The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the anti-Japanese prejudice that followed, would change everything. That it was a time of confusion and uncertainty for all does not erase the horribly wrong acts that followed.

|

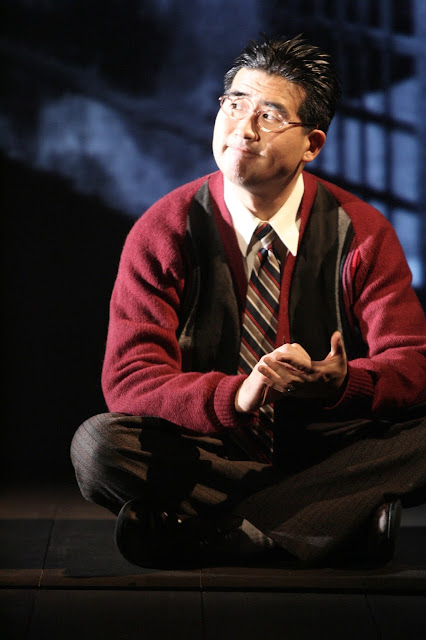

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi

Photo: Michael Lamont |

That change in how the government and society viewed Japanese-Americans and how it impacted the life of a young Seattleite and University of Washington student named Gordon Hirabayashi (1918-2012) is the basis for the play Hold These Truths, which opened on July 17 and runs through August 16. In this one-man show, actor Ryun Yu, in his role as Hirabayashi, tells the true story of how his character came to be one of only three Japanese-Americans to openly defy the government's orders. He refused to report for evacuation to an internment camp. For his defiance, he found himself behind bars. His first conviction was for a curfew violation in 1942 when he stayed at the university's library to study, like other students, instead of going home by 8 p.m. He turned himself in to the FBI and served 90 days in prison. Then, in 1943, his case was appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled against him, resulting in his year-long incarceration in a federal prison.

The U.S. Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit finally overturned Hirabayashi's conviction in 1987, by which time the revelations of previously hidden documents proved that there had never been any military reason for Executive Order 9066, which deprived Japanese-Americans of their rights and freedom, even for those who were born here and had full citizenship. That order, by the way, could have been applied to Americans of German or Italian heritage too, but never was. The majority of the Japanese, naturally law-abiding, complied with the order, just as the majority of non-Japanese citizens also felt the government could not be opposed, even it they truly wanted to oppose it. Then, like now, many seized the opportunity to justify their prejudices and exploit the misfortunes of others. Sometimes even good people, in difficult situations, do not know how, or if, they should become involved, regardless of their beliefs. That is why Hirabayashi, who boldly lived his beliefs, was a hero.

In addition to becoming more educated about American history, those who attend this play will experience being in another's shoes, a reminder of how we humans are far more alike than we think we are. Yu does a fine job of bringing into our consciousness the young Hirabayashi, who was no different any other college student, except for his ethnicity and perhaps the fact that he likely had more knowledge of the Constitution than his peers, and loved it. He was proud to be American born, a citizen, like them. He worried about his grades, wanted to have fun, fell in love, like them. He also became a Quaker and pacifist.

|

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi

Credit: Michael Lamont |

It cannot be easy to be the sole actor on a stage set with nothing but three wooden chairs for props and enhanced by some dramatic lighting, both designed by Ben Zamora, but Yu manages to stimulate the imagination to the point of painting his own scenery with words, under the direction of Jessica Kubzansky. At times, he uses the voices of others with whom he has conversations, and that aspect was the cause of my only slight concern. The accents he used were right on for some of these invisible characters, but as a native of the Northwest, I was puzzled when a milder version of a southern drawl, or perhaps a Hollywood cowboy western drawl, seemed to tint his renditions of our Northwest dialect. Someone else, I know who saw the play more recently did not notice this.

I highly recommend Hold These Truths for its ability to both move us deeply and enlighten us, through personalization, on the topic of one of our nation's most shameful and ugly periods. The seriousness of the subject made the play's many moments of humor surprising and a relief. Yu is convincing as Hirabayashi and will cause you to go home with respect and admiration for this hero, his courage and convictions.

|

Ryun Yu as Gordon Hirabayashi

Photo: Michael Lamont |

Writing this, my memories of three generations of the Matsuda family swirl through my head. No finer, more honorable, members of our community ever existed. I am a better person for having known and worked for them during my childhood. In fact, my father always said, "The Matsudas helped me raise my kids," referring to their examples of a strong work ethic, commitment, fairness, and other virtues. When some other kids quit picking as the summer heat came on and the berries grew smaller and the fields dustier, we stayed, taught that employment was a two-way street. The Matsudas paid us for picking, but they also counted on us to be there to help bring in the crop. Even though our government had let them down, our parents were not about to let us do the same, even on such a small scale.

In the prologue to Looking Like the Enemy, author Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, who was nearly 80 years old when she wrote the book, penned words she might have said to her innocent four-year-old self as seen in an old photo, a happy and secure child.

"Have faith in your family and the ultimate goodness of people," would have been her advice. "Especially have faith in yourself to survive the catastrophic events yet to come. In spite of all the terror, pain, depression, and tears in your future, you will reach a final hopeful conclusion."

I am so glad I saw Hold These Truths. The real facts of history, like a strawberry on a vine too close to the ground, sometimes become soiled with dirt that hides the truth. Only when we brush it away, turn it over, examine it's shiny redness in the honest light of the sun, then taste it for ourselves, can we perceive whether it is bitter with decay or filled with sweetness. The lives of all people, and the nations they live in, always contain a portion of both.